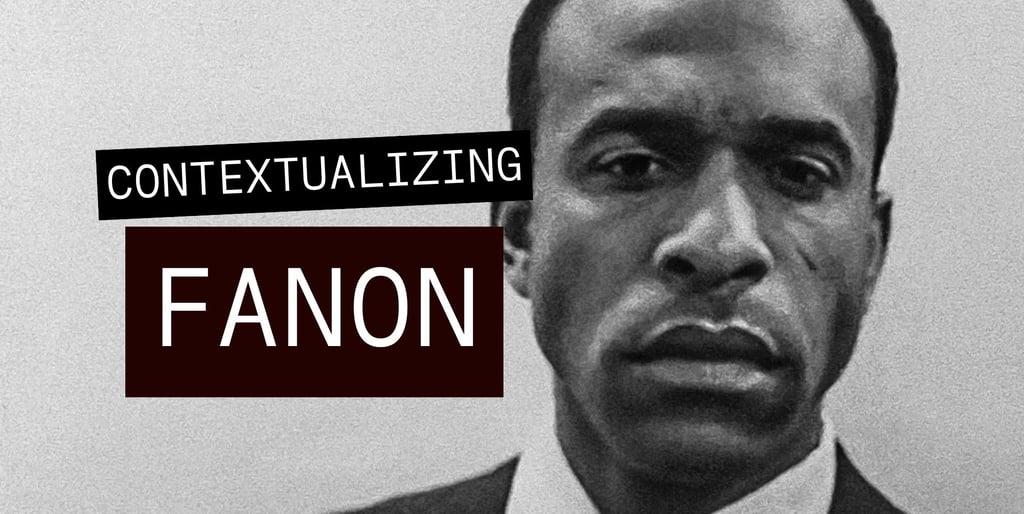

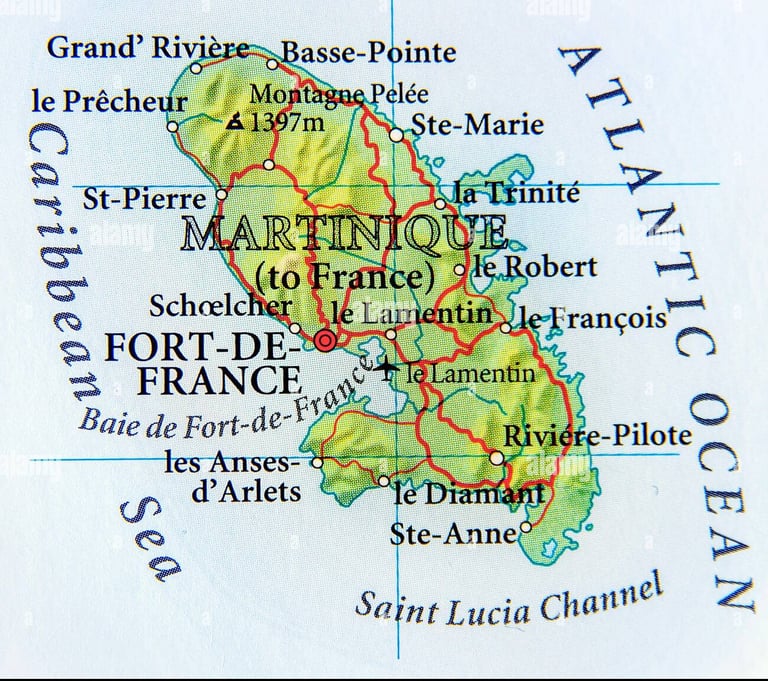

Born on the Caribbean island of Martinique under French colonial rule, Frantz Omar Fanon (1925-61) remains, to this day, one of the most important references on combative decolonisation.

Fanon was an Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist, author, militant, and a strategic figure in connecting liberation movements across many African countries. His body of work is deeply informed by his lived experiences and context. As he writes:

“I am a man of my time”.

From serving in the French army during World War II to becoming a medical doctor in France, and later joining the Algerian Liberation Front (FLN – Front de Libération Nationale), these experiences became material for Fanon's deeper inquiry into identifying and challenging the harms created by European colonialism across all aspects of society, including health and culture, which have long sabotaged people's liberation and sovereignty. Fanon acknowledges that decolonisation requires both psychological and political commitment.

Frantz Fanon and the medical team at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria, where he worked from 1953 to 1956. (Wikimedia Commons)

Fanon’s family occupied a social position within Martinican society that could reasonably qualify them as part of the black bourgeoisie. Members of this social stratum tended to strive for assimilation, and identification with white French culture

Fanon was raised in this environment, learning France’s history as his own, until his high school years when he first encountered the philosophy of negritude, taught to him by

Aimé Césaire, Martinique’s other renowned critic of European colonization.

Fanon left Martinique at the age of 17 years old to fight with the Free French forces during World War II. Being in the French army, Fanon was able to identify many cultural dynamics that were reinforced through French colonies, and many of the power dynamic and colonial fantasies around these dynamics.

At the age of 21, moved to Lyon, France, where he went through medical training and became a psychiatrist. During his time in Lyon, Fanon also studied literature, drama and philosophy. In 1949, he wrote the plays The Drowning Eye (L’Oeil se noie), and Parallel Hands (Les Mains parallales), that were only published in French in 2016, showing a more experimental side of Fanon’s writing.

In 1952, he published his first book,

Black Skin, White Masks

in which he denounces the many layers of European colonial harms in social dynamics, social structures, penetrating and confusing the image of one’s self, desires and their relations. In this book, Fanon names and explains many mechanisms and harmful impacts of ongoing colonisation and how coloniality is violently designed to be hidden in plain sight behind “good intentions”.

After Lyon, at the age of 29 years old, Fanon became chief of staff for the psychiatry ward of the

Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria, in 1954

the same year that marked the eruption of the Algerian war of independence against France, an uprising directed by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and brutally repressed by French armed forces.

Working in a French hospital in Algeria, Fanon was increasingly responsible for treating both the psychological distress of the soldiers and officers of the French army who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance and the trauma suffered by the Algerian torture victims.

During this time, Fanon joined the Algerian Liberation Front (FLN), contributing to its newspaper, al-Moujahid.

Fanon recognises how coloniality is cultivated in behaviours and internalised through many layers of trauma and reinforcement systems. Psychological decolonisation is the first step: to acknowledge colonial trauma without becoming trapped in victimisation or the double-narcissism dynamic that coloniality creates. In his work, we find the many psychological traps designed to keep us away from our own liberation process. He exposes how coloniality is embedded in modern healthcare practices, in our notions of identity, and in how we relate to one another, including through culture.

Fanon’s writing is an invitation to revisit our own experiences from a different perspective. Through deep observation, analysis, and embodiment rooted in his own life, Fanon reveals the dissonance and double standards that permeate colonial discourse. He shows how colonial violence is enacted in everyday life in ways that appear “normal,” thus rendering colonial harms invisible over the long term. Fanon makes it clear: this is not an exception in the system, but a feature of colonial design.

By returning to historical context, Fanon makes the colonial white gaze visible and shows how it has shaped and sustained infantilised, narcissistic behaviours through colonial structures, maintaining a status quo built on fragile egos in power. Through his writing, Fanon shares an analysis of how these collective dynamics shape our perceptions of self, desires, ways of doing, imagining, and relating.

Fanon exposes, with surgical precision, the anatomy of colonialism. He reveals its patterns: habits, behaviours, and narratives cultivated and reinforced by colonial mechanisms such as institutional structures, normative standards, and systems of punishment.

From good intentions to academic dissociation and colonial selective blindness, Fanon identifies how colonial strategies create confusion that reinforces dependency. These strategies feed on manipulation, exploit vulnerability, and undermine both individual and collective liberation, making sovereignty seem impossible. For Fanon, liberation requires both psychological and political engagement.

In many of his writings, Fanon speaks to the importance of being part of a community of practice, rooted and grounded in its context. He often warns of the traps that emerge when we fail to recognise our own biases, cultural and historical context, and positionality. Embodiment is what keeps us grounded: listening, communicating, learning, unlearning, and relearning. To do this in a committed community is to support one another in going deeper into these processes. Colonialism relies on isolation, dissociation, and denial. To reclaim embodiment committed to decolonisation is to access a kind of knowledge that the ego fears, because it reveals truths the ego has tried to lock away. In the body, through the body, and with the body is where we can find both desire and resistance. Individually and in our collective relations.